Oberon: Fairy King and Familiar Spirit

2/3/2020

0 Comments

None of Shakespeare’s stories are original. They are all products of their time. The character of his fairy king Oberon, for instance, can be traced to cultural trends of the time. Alberich was originally a character from German mythology, a treasure-guarding dwarf who opposes Siegfried in the Nibelungenlied - an epic from around 1200, based in oral tradition. He was a prominent character aiding the hero of the epic Ortnit , around 1230. In Norse his name was Alfrikr, and in Old French, Alberon or Auberon.

As Oberon, he appeared in Huon of Bordeaux, a work possibly completed from around 1216 to 1268. Here, he is a hunchback, three feet tall, but very beautiful (having been cursed by a miffed fairy godmother, not unlike Sleeping Beauty). He rules a city named Momur and comes to the aid of the hero, Huon. This chanson de geste , or song of heroic deeds, was widely circulated, translated and adapted throughout Europe. Oberon was occasionally connected to Morgan le Fey at this point in his history. In the Roman d’Auberon, a later addition to the Huon story, he was her son.

A 1543 translation by John Bourchier popularized the story of Huon in English. There was also a play adaptation, Hewen of Burdoche, produced in 1593, which would have popularized the name.

In 1589, the writer Edmund Spenser presented Queen Elizabeth with the first three books of his master work, The Faerie Queene . Spenser represented Elizabeth in several flatteringly portrayed nobles and heroines. One of them is the fairy queen Gloriana, daughter of Oberon (who, in this allegory, stands for Henry VIII). The book even references Huon in connection.

Then there was “The Scottish Historie of James the Fourth, Slaine at Flodden Entermixed with a Pleasant Comedie, Presented by Oboram King of Fayeries.” This play was written about 1590 by Robert Greene, but not printed until 1598. The title is apparently a mistake, as the fairy king is referred to as “Oberon” or “Aster Oberon” in the actual play.

In 1591, on tour, Elizabeth was greeted by a performance formally titled “The Honorable Entertainment given to the Queen’s Majesty in a Progress, At Elvetham in Hampshire, by the Right Honorable Earl of Hereford." This was a masque, a form of courtly entertainment heavy on flattery, addressed to Elizabeth as she watched. In the play, classical Greek gods and nymphs practically worshiped her. Amidst dancing, music, and elaborate set pieces, an actress portraying Fairy Queen “Aureola” presented Elizabeth with a flowery garland from “Auberon, the Fairy King.”

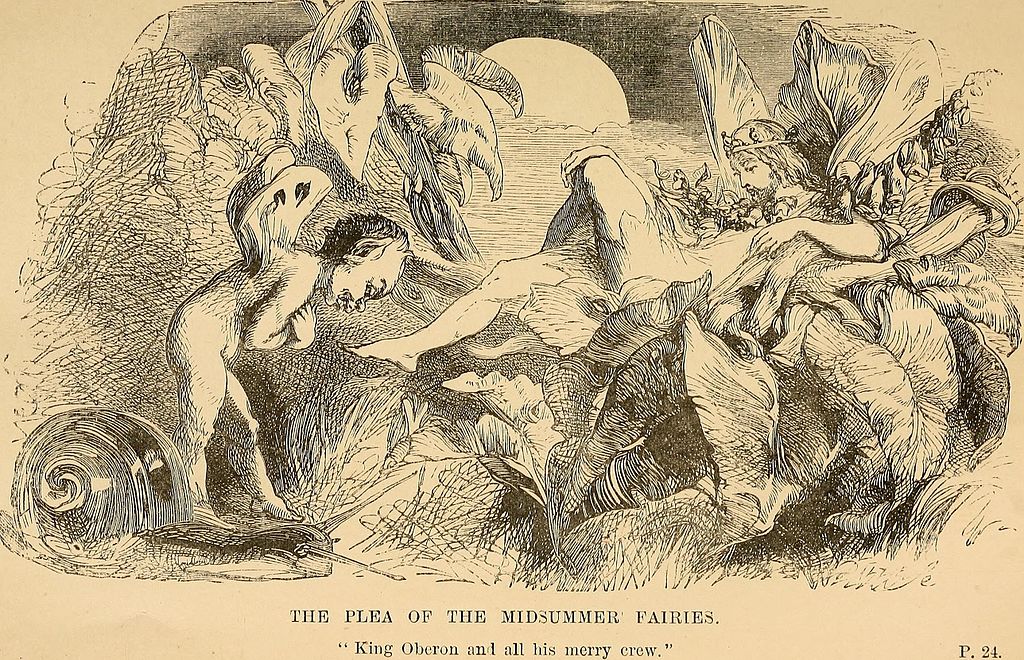

In 1595 or 1596, Shakespeare brought out A Midsummer Night’s Dream, making Oberon and Titania the quintessential fairy royalty forevermore.

Or Oberon, anyway. Although he was apparently firmly fixed in people’s minds as the Fairy King, it seems this may not have been due to Shakespeare. Titania did not yet enjoy the same status. While other poets did use Oberon as a fairy king, they often gave him a different queen.

The play “The Fairy Pastoral” by William Percy (1603), intended for King James, portrays Oberon ruling over a realm named Obera, overseeing other fairy princes like Orion and princesses like Hypsiphyle. There are strong similarities to A Midsummer Night’s Dream in plot and setting as well as some lines. But Oberon’s wife is Chloris - a fairy queen “stickt with Flowres all her body.” Chloris is the name of a Greek nymph or goddess associated with flowers and spring.

In 1627, Michael Drayton’s poetry including the comedic Nymphidia made Oberon truly comedic - an ineffectual bumbler of microscopic size whose wife Mab is running around behind his back. The fae here are no longer threatening even in the slightest. Notice that Mab is still Shakespearean, although from a different play. Drayton may have used the name of a different Shakespeare fairy because it fit better with the cutesy monosyllabic names he chose for his fairy court - “Fib and Tib, and Pinch and Pin, Tick and Quick, and Jil and Jin, Tit and Nit, and Wap and Win.” Also, Shakespeare’s Mab better fits with the extreme miniature of the Nymphidia poem. Mab was by far the most popular fairy queen in the years following Shakespeare.

In other cases, Oberon appeared with no apparent wife in tow. As “Obron,” he shows up in “The Parliament of Bees,” a poem by John Day written probably between 1608 and 1616 and published in 1641. Here he is not only king of the fairies, but also ruler over the bees. Given that he goes fox-hunting, he is evidently larger than Draytonian fae.

Oberon - or “Obreon” - featured in a tract titled “Robin Goodfellow: his mad prankes, and merry Jests.” Here, his only apparent significant other was an unnamed human woman, with whom he fathered Robin Goodfellow. Although the surviving copy was dated 1628, collector James Halliwell-Phillipps believed that it had been printed before, and that it could predate Shakespeare’s writing.

Laura Aydelotte points out that in Germanic epics, the Huon cycle, and A Midsummer Night’s Dream , common threads connect Alberich and Oberon. The character consistently serves to bring lovers together, and is also frequently said to be from India or the East. Oberon’s mixed role lets him play a kindly helper, a trickster, and a regal otherworldly ruler.

However, Oberon had another side as well. Even while used in popular English literature - often to flatter or parody English royalty - a near-identical name appeared in books of witchcraft, as Oberion or Oberyon.

Monk-turned-amateur diviner William Stapleton confessed to calling up the spirits of “Andrew Malchus, Oberion and Inchubus” in hopes of finding buried treasure. Oddly, Oberion refused to speak when summoned; Stapleton claimed this was because the spirit was already bound to Cardinal Wolsey. The date of Stapleton’s trial is unclear, but he lived until 1544. In 1568, Sir William Stewart of Luthrie and Sir Archibald Napier faced charges of (among other things) calling upon a spirit named Obirion to divine the future. Emma Wilby listed “Oberycon” as the name of a witch’s familiar in her book Cunning Folk and Familiar Spirits.

In 1613, a pamphlet was printed entitled “The severall notorious and lewd Cousenages of John West and Alice West” - a couple of con artists who duped people with promises of riches, not unlike a Nigerian Prince scam except their Nigerian Prince was fairy royalty, sometimes portrayed by accomplices in costume. Oberon’s name is mentioned as king of the fairies in Chapter 2, and the Wests’ targets seemed eager to believe that Oberon and his queen were both real and ready to contact them.

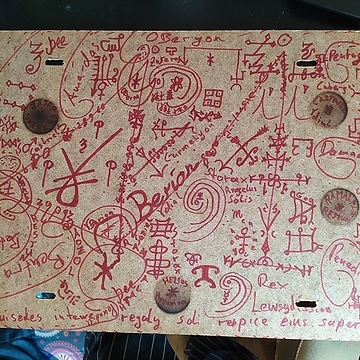

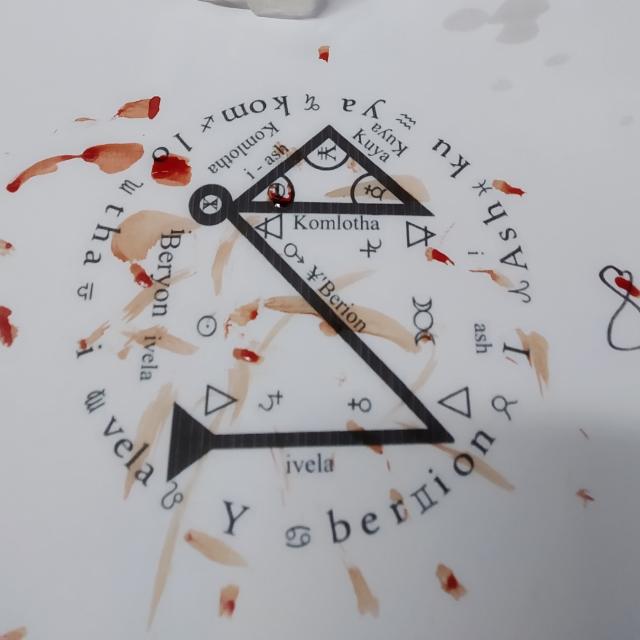

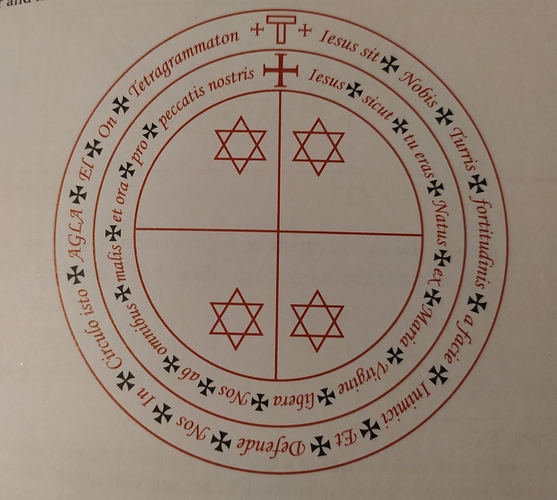

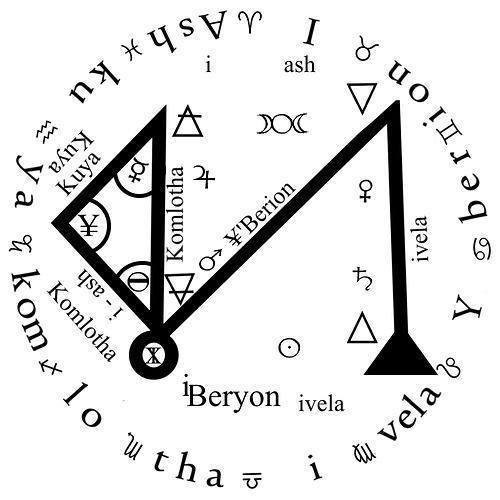

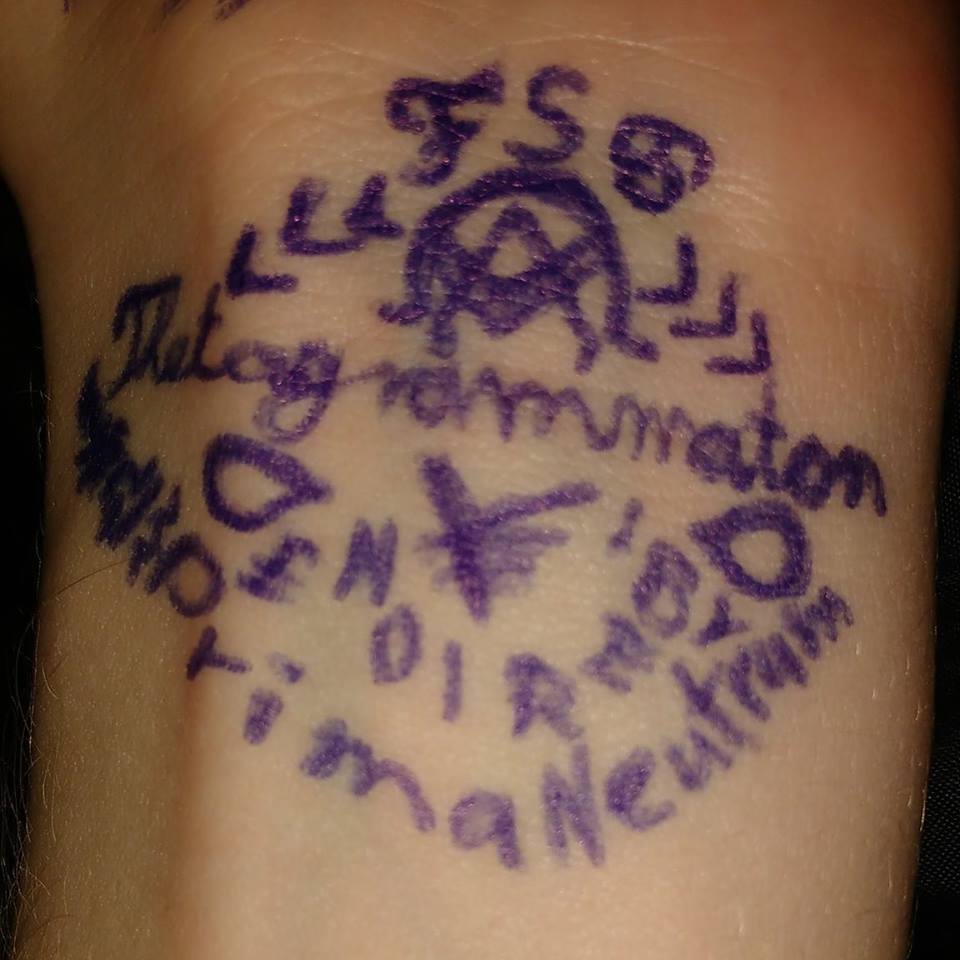

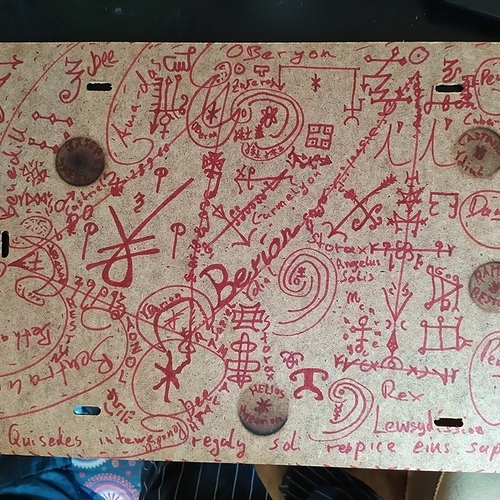

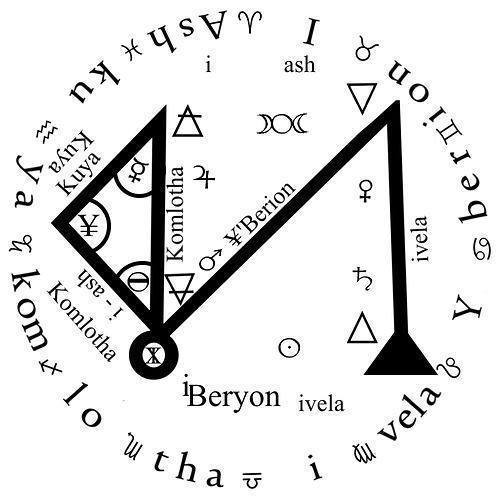

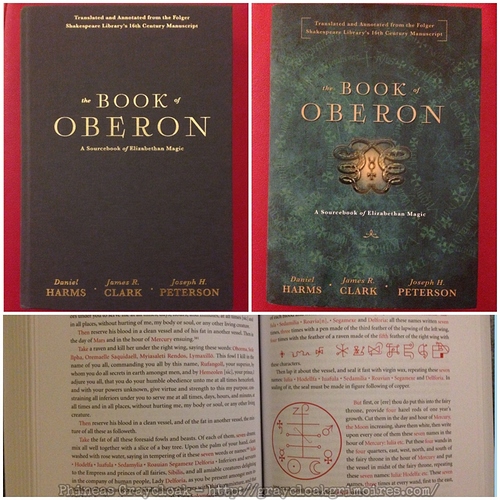

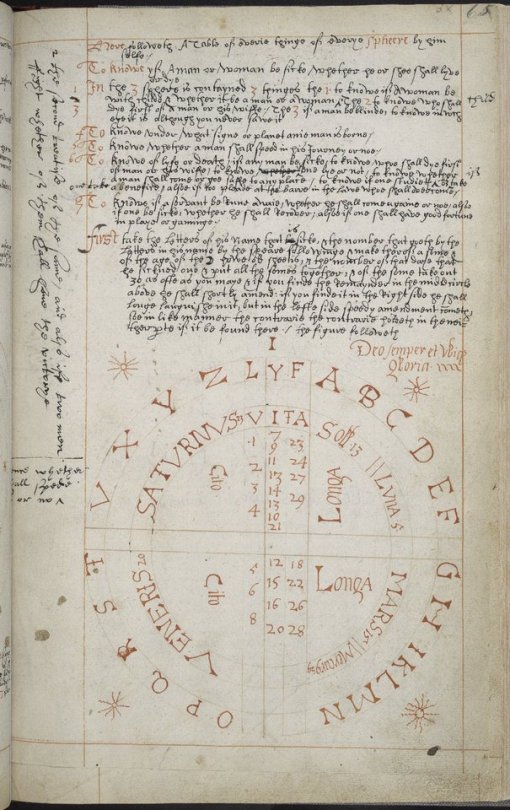

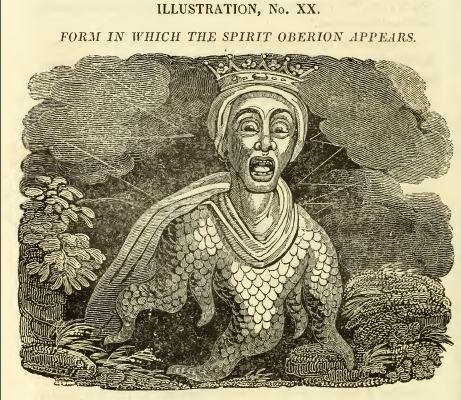

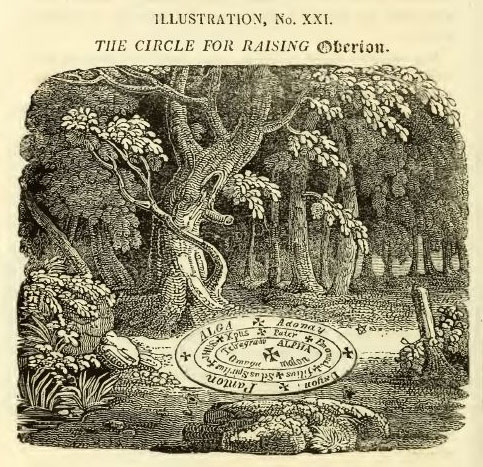

One grimoire that mentioned Oberion was the Liber Officiorum Spirituum , or Book of the Office of Spirits, dating to the 1500s. When drawn, he sometimes resembled a kind of floating genie. He was sometimes accompanied by a fairy queen named Mycob - as in Sloane MS 3824 (1649), where they are the “supreme head” over “Those Kind of Terrestrial spirits … vulgarly Called of all people generally Fairies or Elves.” There are also seven “sisters” who some readers have interpreted as Oberion and Mycob’s daughters. Might Mycob be a form of Mab? Perhaps, but the name also appears as Micol or Michel. Tytan or Titem, similar to Titania, is also an occasional personage in these grimoires.

Oberion, who appeared crowned and regal, knew secrets of the natural world - including where to locate buried treasure or turn invisible. In Arthur Gauntlet’s grimoire, from the 17th century, he had lieutenants: Scorax, Carmelyon, Caberyon, and Seberyon. Spellings abounded. Spelling variants were common. By 1796 in the Wellcome MS 4669, a French manuscript, Arthur Gauntlet’s spells appeared with Oberion replaced by Ebrion (see Rankine, Grimoire ).

However, this Oberion sometimes seems more associated with demons than with fairies. In one manuscript, Oberion is listed with Lucipher and Satan on one page, while Mycob and fairy beings are kept to a separate page. Oberion is the pivotal point where demons are followed by fairies.

Contrast the Oberon of A Midsummer Night’s Dream , who - when warned that dawn approaches and the evil spirits and ghosts are hurrying to hide from the light - responds rather defensively, “But we are spirits of another sort.” He does not fear the light. He’s a powerful being with control over nature, but not an evil spirit. Similarly, Huon’s Oberon must specifically say, “I was never devyll nor yll creature.” He also speaks such Christian exclamations as “God keepe you all!” Upon his death, he is “borne in to paradyce by a great multytude of angelles sent fro our lord Iesu chryst.” Both Oberons are carefully distanced from sorcery and witchcraft. If not saintly Christians, they are at least good spirits.

There was interplay between the fairies of witchcraft and the fairies of literature. They may have diverged, but still continued to influence each other. Oberon/Oberion is not the only fairy to also sort of appear in spells. Numerous variations of Robin (as in Robin Goodfellow) appeared as the names of reputed witches’ familiars. Emma Wilby connected a number of familiars to fairies – such as Hob/Hobgoblin, Browning/Brownie), and Piggin/Pigwiggin.

Sybillia (also Sibyl or Sebile) was a sorceress, fay and temptress in medieval legend from Britain to Italy. She even appears in the Huon cycle as Syble, one of Oberon’s subject rulers. Like Oberon, she also made it quite a few grimoires. Sibylia was listed among fairy queens by Reginald Scot in the Discovery of Witchcraft (1584); Scot even parodied a spell to summon this fairy lady.

Overall, my favorite thing that I’ve learned about Oberon while working on this post is the probably origin of his name. Alberich or Alfrikr translates to alf (elf) + ric (ruler or mighty). Oberon is a French diminutive. So the archetypal fairy king has a name that translates literally to “Fairy King.”

Sources

- Aydelotte, Laura. ‘A Local Habitation and a Name’: The Origins of Shakespeare’s Oberon. Shakespeare Survey: Volume 65, A Midsummer Night’s Dream . Ed. Peter Holland. 2012.

- Brock, Michelle D. Knowing Demons, Knowing Spirits in the Early Modern Period . pp. 67-68.

- Burns, Teresa. “An Introduction to the Book of Magic, with Instructions for Invoking Spirits, etc.” Journal of the Western Mystery Tradition No. 26, Vol. 3. 2014.

- Fletcher, Jefferson B. “Huon of Burdeux and the Fairie Queene.” The Journal of Germanic Philology, Vol. 2, No. 2 (1898), pp. 203-212

- Halliwell-Phillipps, James Orchard. Illustrations of the Fairy Mythology of Shakespeare . 1853. “The Cozenages of the Wests,” p. 181ff.

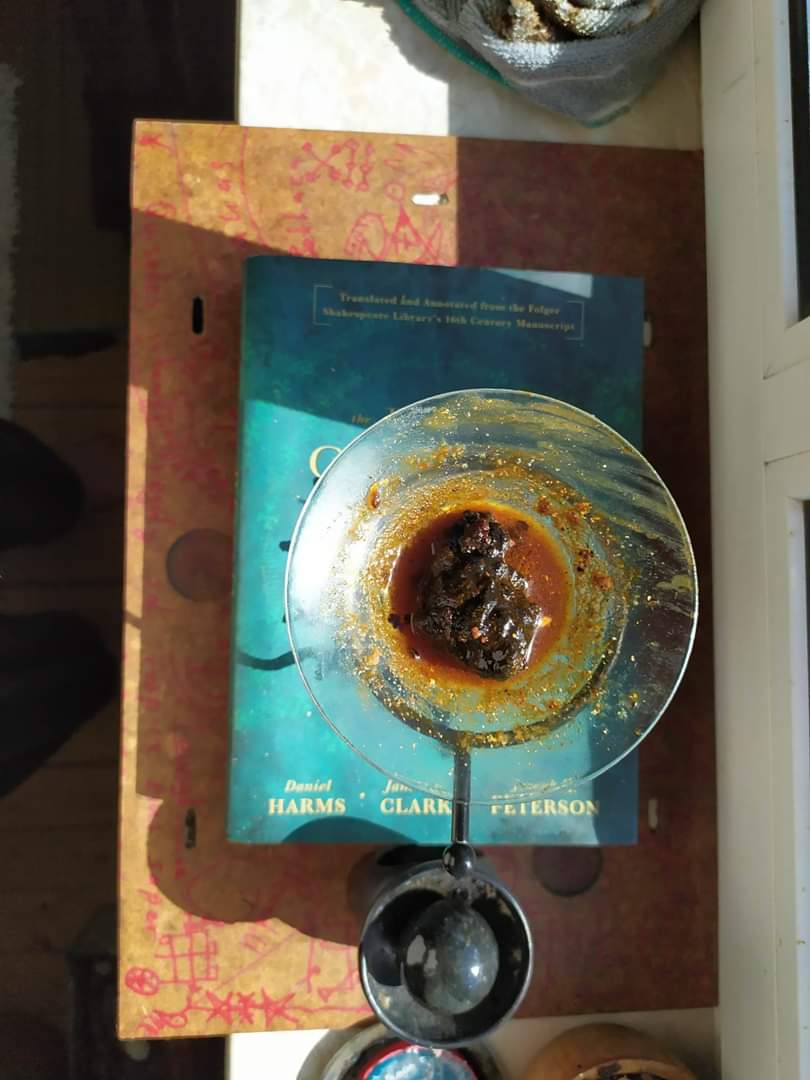

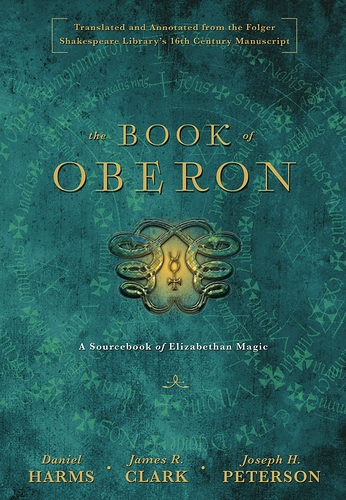

- Harms, Daniel. The Book of Oberon: A Sourcebook of Elizabethan Magic . 2015.

- Rankine, David. The Book of Treasure Spirits . 1998.

- Rankine, David. The Grimoire of Arthur Gauntlet. 2011.

Text copyright © Writing in Margins, All Rights Reserved

Sincerely,

OBoryif

![]()

![Fairy Tail [AMV] - Mard Geer vs. Celestial Spirit King / Lucy vs. Jackal - DIE FOR YOU](https://img.youtube.com/vi/GO5N2UyuQr4/maxresdefault.jpg)

![God Is An Astronaut - Helios | Erebus [Full Album]](https://i.ytimg.com/vi/YjWIAOsndu4/hqdefault.jpg?sqp=-oaymwEmCOADEOgC8quKqQMa8AEB-AHCA4ACxAOKAgwIABABGHIgRygoMA8=&rs=AOn4CLA0HGC4Fkj7ZDuNzmCAPnZ-KZNr0g)

![The Demon Ornias [The Testament of Solomon] (Angels & Demons Explained)](https://img.youtube.com/vi/zgaCjZ1xm6w/maxresdefault.jpg)